[A] report in this month's Economic Journal looks encouraging: professors Andrew Rose and Mark Spiegel say analysis of past history reveals that hosting the Olympics delivers an increase in exports of an extraordinary 20%, a result that is, they say, "statistically robust, permanent and large". But there's a catch: they find that the effect is just as large for countries that have put in a bid to host the Games and failed.They find that the trade benefits accrue to both those countries that win the games and those whose bids lose out.

Rose, from the University of California, Berkeley, and Spiegel, of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, argue that a push to try to host the Games – or other sporting "mega-events" as they call them, such as football World Cups, often goes alongside a conscious decision by a country to tear down trade barriers and play a larger role in the world economy.

They point out that China's negotiations with the World Trade Organisation were completed in 2001, shortly after Beijing won the right to host the 2008 Games; Rome won the 1960 Games in 1955, as Italy joined the UN and began the negotiations that led two years later to the Treaty of Rome.

For Tokyo, Spain and Korea, too, hosting the games went alongside becoming a fully fledged member of the global elite.

Writing for the IMF last year, the authors admit that there is more to the story when it comes to mature economies that are already well integrated into the global economy:

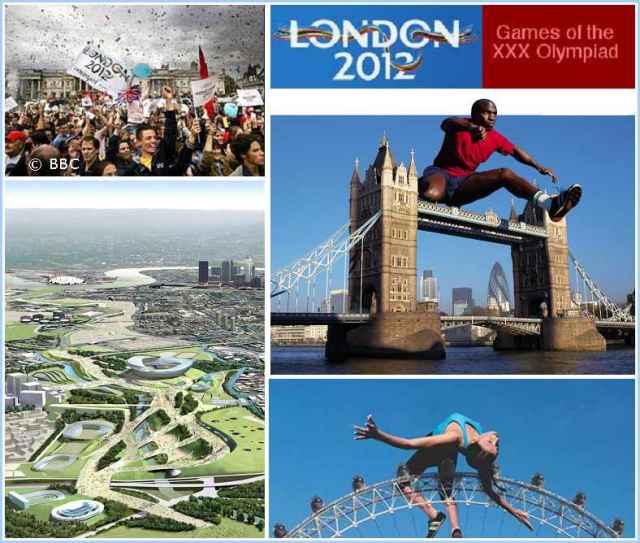

If countries use a bid for a mega event as a signal that they’re opening up to the world, why should anyone want to bid repeatedly for such events? Vancouver hosted the 2010 Winter Games and London will host the 2012 Summer Games. Why should liberal economies ever bid for a mega event? What could the United States have possibly gained from its failed bid for Chicago to host the eighth American Olympiad? Clearly, something else motivates multiple bids from liberalized economies, although the basic argument here could easily be expanded to incorporate multiple bids in an environment where reputation depreciates over time and needs to be reinforced with repeated signaling. In addition, other paths can be used to signal international liberalization. What’s so great about hosting a sporting mega event? There’s clearly more to the story, and much room for future research. Still, our argument seems intuitive, especially when applied to emerging economies on the verge of establishing themselves as international players. Sochi, Russia, is hosting the 2014 Winter Olympics; the 2010 World Cup is being held in South Africa. For such countries, and perhaps for Brazil, hosting a mega event amounts to a clear declaration that the country is becoming a committed member of the international community. The associated benefits may more than offset the staggering costs of hosting the games.The IMF survey contains several pieces which together explain that there are better and worse outcomes associated with hosting the Olympics. London 2012 seems to appreciate many of these lessons, so much so in fact, that organizations are fighting over what to do with the infrastructure after the games are over.

0 comments:

Post a Comment