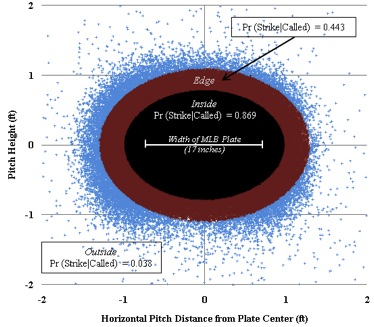

The study uses a large database of pitches in all baseball games from 2004-2008 to compare umpire judgment function of the “race” (white, black, Hispanic, Asian) of the umpire and the pitcher. The study finds a small but real bias against pitchers when the umpire and picture are of different races. Interestingly, the study also finds that in such circumstances pitchers adopt strategies that allow umpires less discretion, such as by avoiding throwing pitches that “paint the edges” of home plate. The authors argue that such strategies have economic consequences and also make bias harder to detect.

The fact that there is a bias detected as it has something to do with race is interesting but not the most significant conclusion of the study. I would guess that if the authors had looked for other sources of bias – such as whether tall umpires favor tall pitchers, or mustachioed umps favor pitchers with facial hair – they would have found it. Bias is a part of human judgment, and if anything, the very small degree of racial bias is itself noteworthy even if troubling by its nature.

The most important finding of the study is that when umpire performance is evaluated against an external standard -- in this case the now-defunct QuesTec umpire evaluation system used by MLB through 2008 -- the bias goes away. The bias also goes away when the game is played before a large crowd or when the pitch matters in the sense that it could be the last of an at-bat. Older, more senior umpires also express little bias, perhaps the authors suggest reflective of a winnowing process in umpiring ranks. Evaluation and accountability are thus shown to be key factors in eliminating bias in subjective judgment.

Here is a key excerpt from the paper:

Our first observation is that pitchers who match the race/ethnicity of the homeplate umpire appear to receive slightly favorable treatment, as indicated by a higher probability that a pitch is called a strike, compared to players who do not match. Although this confers an advantage to some players at the expense of others, the effect we document here is small, on average affecting less than a pitch per game. Much more interesting are situations when and where the effects are strongest. Roughly one-third of the ballparks we study contained a system of computerized cameras (QuesTec) used to evaluate the umpires, comparing their ball/strike calls to a less subjective standard. Umpires have strong incentives to suppress any bias in such situations, as the QuesTec evaluations are important for their own career outcomes. With such explicit monitoring, evidence of any race or ethnicity preference vanishes entirely.A study such as this is only possible because of the magnitude of quality data that is available to the researchers:

We find similar effects with implicit monitoring; when a game is well attended (and presumably more closely scrutinized), or when the pitch is pivotal for an at-bat, race/ethnicity matching again plays no role in the umpire’s evaluation. In situations where the umpire is neither explicitly nor implicitly monitored, the effect of the bias is considerable. As an example, a Hispanic pitcher facing a Hispanic umpire in a low-scrutiny setting (e.g., no cameras, poorly attended) receives strikes on 32.5 percent of called pitches, which drops to 30.0 percent if a black umpire is behind the plate.

There are 30 teams in Major League Baseball, with each team playing 162 games in each regular season. During a typical game each team’s pitchers throw about 150 pitches, so that approximately 700,000 pitches are thrown each season. We collect pitch-by-pitch data from ESPN.com for every regular-season MLB game from 2004–2008.4 Our final dataset consists of 3,524,624 total pitches.The authors suggest that any problem of bias that they document in the recent historical data may now be solved:

[T]hese findings imply that the particular impacts of racial/ethnic match preferences in baseball may now have been vitiated, since beginning in 2009 all ballparks are equipped with QuesTec or similar technologies.QuesTec is no longer used. Instead MLB relies on Zone Evaluation, a technology which was developed by Major League Baseball Advanced Media and Sportvision.

The significance of this paper however goes well beyond balls and strikes. The paper suggests that if you want to address systematic bias in subjective decision making, then pay close attention to decisions, use evaluations against an external metric to assess the decision maker performance with respect to performance objectives and ensure that decision makers are aware of the evaluation criteria.

Roger did the authors also take a look at whether the pitcher that was getting the favorable calls also has a reputation of very good control? A good example of this from the 1990's was Mike Maddox of the Atlanta Braves. During telecasts they would show that the home plate ump was more likely to call a close pitch in Maddox's favor over a pitcher that isn't considered to have good control. The pitch was in the same location but Maddox got it called a strike where his opponent's pitch was called a ball.

ReplyDeleteAnother thing to look at is that if one team is pounding another and it gets late in the game, the Umps will widen the strikezone against the winning team to get the game moving along.

These points come from the perspective of someone that was a pitcher up through High School and whose coach all through Little league and up was a former Major League pitcher and played with and against former minor league players for years in the Navy. They are also well known "biases" among baseball players.

As to finding that any "bias" disappears when things are at the end and on the line is not surprising since MLB has pounded umps to make sure they don't decide a game the players do. it's kinda similar to how in soccer you very rarely see a ref call a PK in the last minute of a 0-0 game.

So the bias is less than a pitch per game? Could this measured bias be due to the very large sample size? Just as small samples sizes cause problems in statistics, large samples can as well. In large sample sizes, you can find statistical significance where there is no practical significance. That is, the 'bias' may be a product of the analysis and not of the umpire's judgement.

ReplyDeleteA related problem is that in any 'finding racial bias' study, we can make a reasonable assumption that the authors of the study went into it looking for bias. When is the last time you saw a news article "Study Shows No Racial Bias in xxx?" Once you acknowledge that researchers go into a study looking for a particular result, it is reasonable to question the nature of the analysis. Did they use one statistical tool, find no bias, and shift to another method? There is a reason why the Analysis section of a paper is written AFTER the work is completed. An honest way of doing it would be to require a Methods and Analysis section to be submitted before the work was started. That would prevent data mining and analysis shopping for significant results.

Of course, the 'less than one pitch per game' result has further ramifications. One pitcher rarely pitches an entire game. Relievers often pitch a single inning each, meaning that it would take more than nine games for the claimed racial bias to show up once. If we were talking about racial bias, and not a numerical bias of outcomes, wouldn't you expect it to show up by appearance, rather than by pitch? Black baseball pitchers are black all the time, not just once every nine-ten games.

This factor and the large number issue mentioned above both point to the overriding issue of statistics - there's a difference between statistical significance and subject significance. When statistical significance has no practical effect on your subject, it should be ignored. All too often, in academic publishing, this prime rule is often ignored.