Indicted FIFA officials and co-conspirators engaged in 12 "schemes" as alleged by the US Department of Justice (here in PDF). The 14 indicted individuals together face 47 criminal counts against them.

I have gone through the 47 counts to the relevant 12 schemes. It seems interesting (to me at least) that there are four schemes which have no associate criminal counts. I am not an expert in criminal law, so I can't judge the significance of schemes without counts.

It is interesting because one of the schemes (#7 - the 2010 FIFA World Cup Vote Scheme) is the one that alleges (and now apparently confirmed from South Africa) that in 2008 FIFA sent $10 million of South Africa's FIFA funds to host the 2010 World Cup to Jack Warner, as a follow up payment in exchange for his 2004 vote for South Africa to host the event.

Is there no count associated with this scheme because:

a. No US laws were violated?

b. Laws were violated and charges are pending?

c. Laws were violated and this will be the subject of future arrests?

d. This is under Swiss jurisdiction?

e. It is simply context?

f. Something else?

Any thoughts?

Sunday, May 31, 2015

Where to Start on Sports Governance?

I was at a neighborhood picnic last night and everyone wanted to talk to me about FIFA. It is great to see such interest in the topic. There were lots of questions, like: What is FIFA anyway? Why is it so hard for anyone to influence them? Aren't they a part of the United Nations? And so on. These are the same sorts of questions that I've been asked by media on 5 continents since the DOJ indictments last week.

It turns out that there are lots of questions like these and not many places to go for ready answers. The media coverage of FIFA has been excellent and offers some great resources for people to learn more about sports governance.

In this post I am going to do the professorial thing, being a professor, and offer some readings. I'll be happy to add to the limited number of pointers presented below and take recommendations. There is a substantial, and sprawling, literature on aspects of sports governance. Much of it is technical and wonky, and it often is narrowly focused on topics like the case of Lance Armstrong, concussions in the NFL or the history of the Olympics.

So consider this post a pointer to some scene setting perspectives. It is impossible to do justice to the field in a single post. In spring of 2016, I'll again be teaching Introduction to Sports Governance here at the University of Colorado-Boulder and I will again share my syllabus (with recommendations welcomed!).

I'll start with two pieces of mine, which were written specifically to address some fundamental questions of the sort that my friends were asking me last evening. Both are peer reviewed papers, but hopefully (if I did my job) they are broadly accessible and readable.

The first paper is titled "Obstacles to accountability in international sports governance" (here in PDF) and was written earlier this year by invitation of Transparency International as part of their "Corruption in Sport Initiative." TI will ultimately have 50+ articles on various dimensions of this topic, which may serve as a definitive resource on the topic. My paper looks at issues broader than just FIFA, which are characteristics of institutions of international sport governance more generally.

Here is how my article begins:

To understand why international sport organisations are so often the subject of allegations and findings of corruption it is necessary to understand the unique standing of these bodies in their broader national and international settings. Through the contingencies of history and a desire by sports leaders to govern themselves autonomously, international sports organisations have developed in such a way that they have less well developed mechanisms of governance than many governments, businesses and civil society organisations. The rapidly increasing financial interests in sport and associated with sport create a fertile setting for corrupt practices to take hold. When they do, the often insular bodies have shown little ability to adopt or enforce the standards of good governance that are increasingly expected around the world.A second article of mine focuses on FIFA. I started it in 2010 after the various World Cup site selections scandals started being reported in the media. The paper was the result of my own effort to answer the question that is the paper's title: "How can FIFA be Held Accountable?" and is here in PDF.

This short article describes why improved governance is needed and why it is so hard to achieve. First, it recounts a number of recent and ongoing scandals among sports governance bodies. Second, it discusses the growing economic stakes associated with international sport. Third, it provides an overview of the unique history and status of international sports organisations, which helps to explain the challenge of securing accountability to norms common in other settings.

Here is the abstract:

The Fédération Internationale de Football Association, or FIFA, is a non-governmental organization located in Switzerland that is responsible for overseeing the quadrennial World Cup football (soccer) competition in addition to its jurisdiction over other various international competitions and aspects of international football. The organization, long accused of corruption, has in recent years been increasingly criticized by observers and stakeholders for its lack of transparency and accountability. In 2011 FIFA initiated a governance reform process which will come to a close in May 2013. This paper draws on literature in the field of international relations to ask and answer the question: how can FIFA be held accountable? The paper’s review finds that the answer to this question is "not easily." The experience in reforming the International Olympic Committee (IOC) more than a decade ago provides one model for how reform might occur in FIFA. However, any effective reform will require the successful and simultaneous application of multiple mechanisms of accountability. The FIFA case study has broader implications for understanding mechanisms of accountability more generally, especially as related to international non-governmental organizations.For those wanting to dig deeper, these papers cite excellent work by several scholars, among them Jean-Loup Chappelet, who has written extensively on the Olympic movement and international sports governance. There are also excellent books about FIFA, most recently "The Ugly Game" by Heidi Blake and Jonathan Calvert.

Perhaps the best one-stop shop for learning more about various dimensions of sports governance is the website of Play the Game, a Danish group focused on governance. The next stop probably should be the resources made available by Transparency International. One can dig much deeper by browsing the journals listed here on "sports management" broadly conceived.

Sports governance is a sprawling area of practice and inquiry. There is some excellent media reporting these days on the subject, which ideally will make more sense if placed into the context of a broader understanding of the issues and history.

Comments, pointers, suggestions encouraged!

Saturday, May 30, 2015

The FA Cup Hurricane Prediction Model

As readers here will know, I have a long-time interest in predictions - how they are made, how they are used and how good they are. Evidence indicates that though we try hard, we are just not very good at making good predictions.

Luckily, in research I did a few years back I appear to stumbled on to an exception. In a paper on mine on our ability to anticipate US hurricane damages 1-5 years in advance (here in PDF), the time scale of predictions offered by the so-called "catastrophe modelling" companies, I discovered a unique relationship between the final score of the FA Cup and the total hurricane damage in the US later that same year.

I explain:

So how have these sophisticated (and costly) predictions done compared to the FA Cup Prediction model from 2008-2014? The table below shows the results.

You can see that the FA Cup model has been twice as accurate as the catastrophe modeling companies in anticipating US hurricane damage.

OK, this is all fun and games, but there is a serious point here to make as well, and it goes far beyond hurricanes to how we produce and think about scientific research that produces predictions about the future.

From my 2009 paper:

Luckily, in research I did a few years back I appear to stumbled on to an exception. In a paper on mine on our ability to anticipate US hurricane damages 1-5 years in advance (here in PDF), the time scale of predictions offered by the so-called "catastrophe modelling" companies, I discovered a unique relationship between the final score of the FA Cup and the total hurricane damage in the US later that same year.

I explain:

Indeed, my own research shows a correlation of 0.33 between the total score in the UK Football Association’s (FA’s) annual Cup Championship game and the subsequent hurricane season’s damage, without even controlling for SSTs, ENSO or the Premier League tables. Years in which the FA Cup championship game has a total of three or more goals have an average of 1.8 landfalling hurricanes and USD11.7 billion in damage, whereas championships with a total of one or two goals have had an average of only 1.3 storms and USD6.7 billion in damage.Of course, anyone with some data and a spreadsheet can mine for relationships. The true test of a prediction is how it does in real-time prediction. Starting 2006, the companies which provide forecasts (or "medium-term outlooks") of US hurricane damage for 5 years into the future consistently predicted that annual hurricane damage would be above average. These predictions are important because they influence everything from global reinsurance to homeowners insurance.

So how have these sophisticated (and costly) predictions done compared to the FA Cup Prediction model from 2008-2014? The table below shows the results.

OK, this is all fun and games, but there is a serious point here to make as well, and it goes far beyond hurricanes to how we produce and think about scientific research that produces predictions about the future.

From my 2009 paper:

The "Guaranteed Winner Scam" Meets the "Hot Hand Fallacy"Enjoy today's game. Let's hope for less than 3 goals, and of course, an Arsenal win!

I am sure that no one would believe that there is a causal relationship between FA Cup championship game scores and US hurricane landfalls, yet the existence of a spurious relationship should provide a reason for caution when interpreting far more plausible relationships. Two simple dynamics associated with interpreting predictions help to explain why fundamental uncertainties in hurricane landfalls will inevitably persist.

The first of these dynamics is what might be called the ‘guaranteed winner scam’. It works like this: select 65,536 people and tell them that you have developed a methodology that allows for 100 per cent accurate prediction of the winner of next weekend’s big football game. You split the group of 65,536 into equal halves and send one half a guaranteed prediction of victory for one team, and the other half a guaranteed win on the other team. You have ensured that your prediction will be viewed as correct by 32,768 people. Each week you can proceed in this fashion. By the time eight weeks have gone by there will be 256 people anxiously waiting for your next week’s selection because you have demonstrated remarkable predictive capabilities, having provided them with eight perfect picks. Presumably they will now be ready to pay a handsome price for the predictions you offer in week nine.

Now instead of predictions of football match winners, think of real-time predictions of hurricane landfall and activity. The diversity of available predictions exceeds the range of observed landfall behaviour. Consider, for example Jewson et al. (2009) which presents a suite of 20 different models that lead to predictions of 2007–2012 landfall activity to be from more than 8 per cent below the 1900–2006 mean to 43 per cent above that mean, with 18 values falling in between. Over the next five years it is virtually certain that one or more of these models will have provided a prediction that will be more accurate than the long-term historical baseline (i.e. will be skilful). A broader review of the literature beyond this one paper would show an even wider range of predictions. The user of these predictions has no way of knowing whether the skill was the result of true predictive skill or just chance, given a very wide range of available predictions. And because the scientific community is constantly introducing new methods of prediction the ‘guaranteed winner scam’ can go on forever with little hope for certainty.

Complicating the issue is the ‘hot hand fallacy’ which was coined to describe how people misinterpret random sequences, based on how they view the tendency of basketball players to be ‘streak shooters’ or have the ‘hot hand’ (Gilovich et al., 1985). The ‘hot hand fallacy’ holds that the probability in a random process of a ‘hit’ (i.e. a made basket or a successful hurricane landfall forecast) is higher after a ‘hit’ than the baseline probability.9 In other words, people often see patterns in random signals that they then use, incorrectly, to ascribe information about the future. The ‘hot hand fallacy’ can manifest itself in several ways with respect to hurricane landfall forecasts. First, the wide range of available predictions essentially spanning the range of possibilities means that some predictions for the next years will be shown to have been skillful. Even if the skill is the result of the comprehensive randomness of the ‘guaranteed winner scam’ there will be a tendency for people to gravitate to that particular predictive methodology for future forecasts.

Friday, May 29, 2015

Productive Debate on FIFA's Future

Now that Sepp Blatter has won a fifth term and the US and Swiss prosecutors are hard at work with who-knows-what-might-happen-next, it might be a good time to debate what kind of FIFA we'd collectively lie to see in the future. Having this debate may prove a challenge.

Consider this very recent tiff.

Over at FiveThirtyEight Nate Silver proposed one model for a new, breakaway soccer association:

But what if you used the 34 OECD members as the foundation of a new football federation? The OECD doesn’t include Russia but does have most of the large European economies, including Germany, the U.K., France, Italy and Spain. It also has the United States and a foothold in the Asia-Pacific region (Japan, South Korea, Australia) and Latin America (Mexico, Chile). These OECD members account for more than 60 percent of the GDP-weighted World Cup audience and about 80 percent of the club-team representation in the 2014 World Cup.Silver's proposal drew the ire of Branko Milanovic, CUNY professor and former World Bank economist:

Convince Brazil and Argentina to join the breakaway foundation, and you’re doing even better. You’d be up to almost 70 percent of the GDP-weighted World Cup audience, and you’d have 11 of the 16 countries that advanced to the knockout stage of last year’s World Cup.

The piece illustrates that a combination of good statistics with lack of knowledge of history, produces useless results. It is as if one were to study today’s racial wage gap in the US without knowing that there ever was slavery.Do go read both pieces in full. Both make some interesting points, but neither really helps to clarify options, much less expand them into new possibilities. A debate over FIFA's future, of course, is one worth having -- and judging by Milanovic and Silver's Twitter exchanges, probably not on Twitter.

But let us consider the key part of Nate’s idea. He thinks that a new FIFA should be formed of the countries that bring most money to the current FIFA and the rest should be left out in the cold. Let the poor countries with awful soccer turfs, with these miserable human creatures that cannot pay $100 per game, stay out on their own, and keep on playing their game on dirt fields, not seen on TV screens or by anyone else except their neighbors. In the meantime, we the new rich and shiny FIFA will come to the game in our Audis and Mercedeses, and play on the impeccable fields full of fun commercials, and shall flood every TV screen of every nation in the world.

The importance of countries reflects, Nate says, how much money they bring to FIFA. If a country is rich, populous and lots of people watch the World Cup, and thus add to FIFA’s revenues, then that country should matter more. OECD is big and rich enough to go it alone.

The essential issue here was well characterized by Stefan Szymanski in an earlier post at Reuters:

Perhaps most worryingly for FIFA and the future of the World Cup, it’s not even clear that people around the world agree on the meaning of corruption. This is a culturally sensitive issue. Kickbacks and bribery are a normal part of doing business in many countries, as documented by watchdog Transparency International. But even within the United States, in many cases it is the norm to pay individuals a gratuity for making things happen. When you tip a waiter or doorman you don’t expect the sum to be public or the transaction to be considered a bribe, even if you follow your tip with “Now please find me the best table.”Options for FIFA's future are not at all comparable, as Silver analogizes, to spinning off the Premier League from lower divisions in English soccer in the early 1990s. Nor is it comparable, as Milanovic has it, to deciding on the proper form of global governance. Such perspectives do more to muddle than clarify.

In northwest Europe and the United States, we have now drawn a sharp distinction between this legal activity and the illegal activity of giving gratuities to public officials or individuals involved in arms-length transactions. Not everyone in the world thinks like this. No doubt there are executives inside FIFA who, until now, have thought of themselves as “clean,” but must be wondering if any of their actions might be actually be legal. After all, the Justice Department says, “this indictment is not the final chapter in our investigation.”

Building a coalition on a global scale — and that’s what the World Cup and FIFA really is — requires immense compromises, and often a willingness not to look too deeply into what is going on. Most people might applaud the Justice Department’s assault on the worst excesses of FIFA. But if this investigation goes much deeper, resistance from the members of the FIFA congress might stiffen. The warring parties might break up into regional blocs, and the World Cup itself might be the victim. If that is the price of justice, some might say, then it is a price worth paying.

FIFA is a sports association, with a long history and complex politics. That people around the world care so deeply about soccer is wonderful. However, considerations of options for improving FIFA won't benefit from oversimplifying the politics and culture, nor from overstating the significance of FIFA's governance structure. And our discussion of options won't benefit from snark on Twitter. Any discussion of FIFA's options going forward must be well attuned to politics, history, culture, data, and realize that people will fundamentally disagree about many of these things.

In fact, achieving disagreement would be a sign of process. At the moment, before (the) other investigative shoe(s) drop(s), we have an opportunity to engage in a thoughtful debate about options for FIFA's future. Clarity on options may prove useful at some point in the future. Big wigs like Silver and Milanovic can help that debate to happen, or not.

Thursday, May 28, 2015

Tuesday, May 26, 2015

Circular and Irrelevant Scientific Reasoning in "Sex Testing" Debates

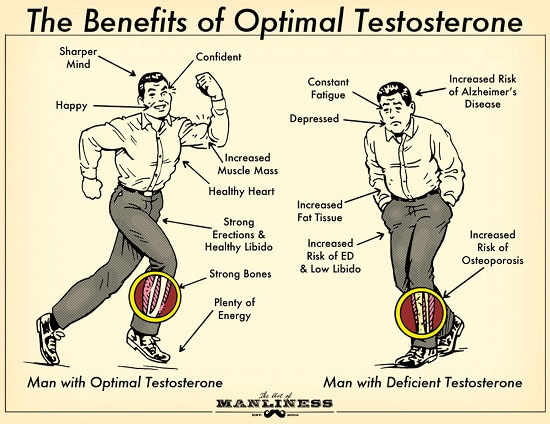

In the current issue of Science Katrina Karkazis and Rebecca Jordan-Young have a Policy Forum on the measurement of testosterone in male and female athletes. The article makes one excellent point but it also confuses issues of sex and gender in the arena of "sex testing" for determining qualification to participate in elite sports as male or female.

First the excellent point.

Karkazis and Jordan-Young observe the fundamental circularity involved in quantifying testosterone levels in male and female athletes. A necessary methodological step is to identify who is male and who is female before doing the comparison. But if testosterone is used as a distinguishing characteristic, then any "scientific" test will simply serve as a mirror to the classification scheme, hence the circularity.

No scientific test can tell us who is male and who is female. Thus, it is confusing for Karkazis and Jordan-Young to engage in a debate over the science of testosterone levels as a marker of sexual categorization. They seem to first accept testosterone as a marker of sexual categorization by challenging the science of testosterone.

I think it is far better to simply point out that the science, while interesting, is just irrelevant. Here is what I write about that in my paper on "sex testing";

Sex and gender are indeed different concepts, and they are not interchangeable. They probably mean to say that "gender identity is the best tool available for distinguishing elite athletes into categories for purposes of competition." But they didn't and this may be confusing to readers not immersed in this issue.

Karkazis and Jordan-Young hint at this more accurate framing in their conclusion when they suggest, quite correctly, that gender is a social construction and so too are the categories that we separate men and women into for purposes of competition. However, once you accept that fact -- and social construction is a fact (for all you post-modernists;-) -- then all of the debate over the science of testosterone as a marker of male-ness and female-ness become pretty much irrelevant.

However, the urge to debate policies through science is a strong one.

First the excellent point.

Karkazis and Jordan-Young observe the fundamental circularity involved in quantifying testosterone levels in male and female athletes. A necessary methodological step is to identify who is male and who is female before doing the comparison. But if testosterone is used as a distinguishing characteristic, then any "scientific" test will simply serve as a mirror to the classification scheme, hence the circularity.

No scientific test can tell us who is male and who is female. Thus, it is confusing for Karkazis and Jordan-Young to engage in a debate over the science of testosterone levels as a marker of sexual categorization. They seem to first accept testosterone as a marker of sexual categorization by challenging the science of testosterone.

I think it is far better to simply point out that the science, while interesting, is just irrelevant. Here is what I write about that in my paper on "sex testing";

While there is an ongoing debate over the effects of testosterone on athletic performance, here I depart from some of the critics of the IAAF policy. I argue that testosterone simply does not matter -- not scientifically -- but practically. Let us suppose for the sake of argument that some women have testosterone levels which fall into a range that is far more populated by men. Let us further suppose that this amount of testosterone can be associated with some greater athletic achievement, say speed or strength. The appropriate response is “so what?”

Imagine the previous paragraph rewritten with “height” substituted for “testosterone.” There are notable examples of female athletes with exceptional height, generally attained only by men, who achieved notable sporting successes. Further, challenging the exact role of testosterone in athletic performance gives standing to the IAAF/IOC policies that they do not deserve. The role of naturally occurring testosterone in a woman is no more significant than hereditary polycythemia. The role of naturally-occurring testosterone in athletic performance is scientifically interesting, but it is inherently no more relevant to athletics policy than any other naturally occurring characteristic of the human athlete, man or woman.

Now the confusing part. Karkazis and Jordan-Young write:

... it is widely recognized in medicine, law, and the social sciences that when people are born with mixed markers of sex (e.g., chromosomes, genitals, gonads), the medical standard is that gender identity is the definitive marker of sex—there is no better criterion.I know (from experience) that the writing of a Policy Forum for Science requires brevity in words and nuance can be lost. But in this case I think that Karkazis and Jordan-Young have sacrificed accuracy for brevity.

Sex and gender are indeed different concepts, and they are not interchangeable. They probably mean to say that "gender identity is the best tool available for distinguishing elite athletes into categories for purposes of competition." But they didn't and this may be confusing to readers not immersed in this issue.

Karkazis and Jordan-Young hint at this more accurate framing in their conclusion when they suggest, quite correctly, that gender is a social construction and so too are the categories that we separate men and women into for purposes of competition. However, once you accept that fact -- and social construction is a fact (for all you post-modernists;-) -- then all of the debate over the science of testosterone as a marker of male-ness and female-ness become pretty much irrelevant.

However, the urge to debate policies through science is a strong one.

Evaluation of Skill in 2014/2015 EPL Predictions

Over at Sporting Intelligence my latest column is up. In it I review the skill of 60 predictions of the 2014/2015 EPL season.

Head on over there to read it, and feel free to return here if you have any questions on comments.

Bottom line? Skillful prediction is really, really difficult,

Head on over there to read it, and feel free to return here if you have any questions on comments.

Bottom line? Skillful prediction is really, really difficult,

Thursday, May 21, 2015

A Problem with 538's NBA ELO Time Series

UPDATE 22 May: FiveThirtyEight doubles down on this flawed methodology with a follow-up post that makes the erroneous thinking inescapable. Not good.

The ESPN website FiveThirtyEight (disclosure: I wrote a handful of pieces for them in 2014) has just put up a time series of ELO rankings for NBA (and also now defunct) basketball teams. The effort is notable but deeply problematic. Consider that the ELO rankings produce the following:

1949 Chicago Stags: 1577 (pictured above)

2015 New York Knicks: 1256

Raise your hand if you think that the 1949 Stags (a fine team no doubt) would be favored to beat the 2015 New York Knicks!

The problem is that ELO is constrained to an average value of 1500 over time, thus removing the signal of any trends, variability or non-stationarity in the league performance.

ELO is a tool for contemporary comparison, and is not well suited for presentation as a time series because the baseline changes over time. I'd guess over the long term it has changed so that teams get better, on average, as compared with those of the past. But certainly there is variation in the overall competitive level of the league, which ELO does not capture.

So when 538 says that the 1996 Chicago Bulls were "the best ever there ever was," what this really means is that they were relatively the best team ever, in comparison to the competition that they faced in 1996. That is a bit different than saying they are "the best that ever was." Producing a time series of ELO is thus fundamentally flawed.

In other words, an average ELO team in 2015 at 1500 is not at all comparable to an average ELO team at 1500 in 1949. The 2015 New York Knicks, as awful as there were in 2015, would probably beat the 1949 Chicago Stags by about 100 points.

Thus, rather than reporting absolute ELO scores 538 might have reported anomalies from the long-term average, to present a team's relative ranking, thus removing the need for consideration of any trend. Not as cool as a long-term ranking, but more accurate.

It is a good first effort, but needs some work!

The ESPN website FiveThirtyEight (disclosure: I wrote a handful of pieces for them in 2014) has just put up a time series of ELO rankings for NBA (and also now defunct) basketball teams. The effort is notable but deeply problematic. Consider that the ELO rankings produce the following:

1949 Chicago Stags: 1577 (pictured above)

2015 New York Knicks: 1256

Raise your hand if you think that the 1949 Stags (a fine team no doubt) would be favored to beat the 2015 New York Knicks!

The problem is that ELO is constrained to an average value of 1500 over time, thus removing the signal of any trends, variability or non-stationarity in the league performance.

ELO is a tool for contemporary comparison, and is not well suited for presentation as a time series because the baseline changes over time. I'd guess over the long term it has changed so that teams get better, on average, as compared with those of the past. But certainly there is variation in the overall competitive level of the league, which ELO does not capture.

So when 538 says that the 1996 Chicago Bulls were "the best ever there ever was," what this really means is that they were relatively the best team ever, in comparison to the competition that they faced in 1996. That is a bit different than saying they are "the best that ever was." Producing a time series of ELO is thus fundamentally flawed.

In other words, an average ELO team in 2015 at 1500 is not at all comparable to an average ELO team at 1500 in 1949. The 2015 New York Knicks, as awful as there were in 2015, would probably beat the 1949 Chicago Stags by about 100 points.

Thus, rather than reporting absolute ELO scores 538 might have reported anomalies from the long-term average, to present a team's relative ranking, thus removing the need for consideration of any trend. Not as cool as a long-term ranking, but more accurate.

It is a good first effort, but needs some work!

Tuesday, May 19, 2015

Gatlin's Geriatric Sprinting Exceptionalism

The graph above shows sprint times for 100m for 10 top sprinters, by age. The data comes from the IAAF (which hosts a fantastic array of easily accessed data). The sprinters include those with the 9 fastest times ever recorded (< 9.84 seconds) plus Carl Lewis. More sprinters could be easily added.

I was motivated to compile the data by this post today by Ross Tucker at his excellent Science of Sport blog. Tucker discusses the interesting case of Justin Gatlin the US sprinter who at age 33 is running faster than he ever did when younger. Gatlin's circumstances are interesting (right euphemism?) because he served a 4-year ban for doping from 2006 to 2010 for steroids. He is of course not the only athlete on this graph who has been punished for doping.

Tucker explains why Gatlin's circumstances provoke interest:

The graph shows that these top sprinters pretty uniformly improved their sprint times until ages 25-27. The average age for career-best time is just over 26 and the average age for 2nd career best time is just under 26. Gatlin's career best (so far) came last week at age 33 and 2nd career best at age 32. At the same meet in Doha that Gatlin won, 39-year old Kim Collins came in 4th at 10.03.

In fact, none of these athletes ran a faster 100m after age 27 than they did at 27 or before (except Richard Thompson who ran faster at 29). Tucker points to a few athletes who had career bests in their 30s. Gatlin, of course, wasn't running (for time) at age 27 since he was serving a doping suspension. We can imagine all sorts of ways to connect the dots between the two red curves in the graph, consistent with a range of possible story lines. Here are a few:

I was motivated to compile the data by this post today by Ross Tucker at his excellent Science of Sport blog. Tucker discusses the interesting case of Justin Gatlin the US sprinter who at age 33 is running faster than he ever did when younger. Gatlin's circumstances are interesting (right euphemism?) because he served a 4-year ban for doping from 2006 to 2010 for steroids. He is of course not the only athlete on this graph who has been punished for doping.

Tucker explains why Gatlin's circumstances provoke interest:

Since his return in 2010, he has run faster every single year, and claimed six of the seven fastest times in 2014. He also had the two fastest 200m of the year, including a double at the Brussels Diamond league event where he ran 9.77s and 19.71s on the same evening.Motivated by Tucker's post I thought I'd look at some data.

Impressive stuff, and just what the sport needs – a challenger to Usain Bolt (and the other Jamaicans) as we build towards the Rio 2016 Olympics, and Bolt’s quest to claim a third sprint double.

Except, there’s that nagging, not insignificant doping problem around that challenger. Gatlin is the problem that will not go away. . . . he is a former doper, dominating a historically doped event, while running faster than his previously doped self.

The graph shows that these top sprinters pretty uniformly improved their sprint times until ages 25-27. The average age for career-best time is just over 26 and the average age for 2nd career best time is just under 26. Gatlin's career best (so far) came last week at age 33 and 2nd career best at age 32. At the same meet in Doha that Gatlin won, 39-year old Kim Collins came in 4th at 10.03.

In fact, none of these athletes ran a faster 100m after age 27 than they did at 27 or before (except Richard Thompson who ran faster at 29). Tucker points to a few athletes who had career bests in their 30s. Gatlin, of course, wasn't running (for time) at age 27 since he was serving a doping suspension. We can imagine all sorts of ways to connect the dots between the two red curves in the graph, consistent with a range of possible story lines. Here are a few:

- He might just be the greatest sprinter in history, in terms of longevity and sustained performance (just look at Usain Bolt's curve), who ran into some really bad luck.

- He might be, as Tucker and others mention as possible, still benefiting from past doping, suggesting that short-term bans aren't really up to the task.

- He might be doping today, and has figured out how to evade the testers.

We will be hearing more about Gatlin and doping to be sure.

A Model for Sharing Licensing Value with College Athletes

On Twitter, Steve Berkowitz (of USA Today @byberkowitz) shared the image above from a presentation given by Doug Allen to the Knight Commission on College Athletics.

The slide shows a proposal for group licensing of players' name and image right. The proposal has a lot in common with an idea that I have aired to model college athlete compensation for their "intellectual property" in much the same way that universities manage IP for professors and other researchers. Allen's proposal suggests that others are also thinking about creative ways to align incentives in a positive way.

Here is my proposal in more detail:

The slide shows a proposal for group licensing of players' name and image right. The proposal has a lot in common with an idea that I have aired to model college athlete compensation for their "intellectual property" in much the same way that universities manage IP for professors and other researchers. Allen's proposal suggests that others are also thinking about creative ways to align incentives in a positive way.

Here is my proposal in more detail:

What the NCAA can learn from Bayh-Dole

College sports are facing a crisis. A group of about two dozen current and former college athletes, led by former UCLA basketball star Ed O’Bannon have sued the National Collegiate Athletics Administration. The athletes argue that licensing revenues generated by the NCAA using the images and likenesses of specific players should be shared with those players. In the coming weeks a federal judge will decide whether to certify the case as a class action, which would then bring into the case many thousands of former and current college athletes.

If that were to occur, then the NCAA and universities could be responsible for paying billions of dollars to college athletes. In 2012, the top 5 college athletic conferences collectively received over $1 billion in television revenue for football and the March Madness spring post-season basketball tournament operates under a 14-year, $10.8 billion television agreement. March Madness alone generated more than a billion dollars in TV ad revenue, exceeding that of the National Football League, the National Basketball Association and Major League Baseball. Johnny Manziel, the Texas A&M quarterback who won the Heisman Trophy last year, generated an estimated $37 million in publicity for his university last year.

With the magnitude of the financial stakes, it is only a matter of time before the dam breaks and the notion of the “scholar-athlete” who plays only for school pride and a scholarship becomes a thing of the past. Rather than wait for a court decision, a labor action by high profile athletes or other possible revolutionary changes, the NCAA and universities can get ahead of this issue by paying attention to the lessons of history very close to home.

In 1980 the US Congress passed what the Economist called in 2002 “possibly the most inspired piece of legislation to be enacted in America over the past half-century.” The Bayh-Dole Act changed property rights with respect to the discoveries made in universities as a result of federally funded research. Prior to 1980 the US government retained ownership of the intellectual property associated with discoveries which resulted from federal research and development. Very few of the patents owned by the federal government were being been commercialized, and policy makers sought a way to better capitalize on the billions of dollars in federal R&D taking place at universities.

Under the law, professors and other university researchers who create intellectual property gain a share in its rewards, thereby creating strong incentives both to discover and to commercialize. In the two decades following the passage of Bayh-Dole US universities increased their patents by 1,000% and added an estimated $40 billion annually to the economy. At the same time, the law ensured that technology transfer activities on campus would be closely monitored to ensure that the mission of universities was not compromised.

So what does Bayh-Dole tell us about college athletics? Several years ago, former Senator Birch Bayh explained why the Bayh-Dole Act works: “it aligns the interests of the taxpaying public, the federal government, research universities, their departments, inventors, and private sector developers transforming government supported research into useable products.”

The NCAA and universities should explore aligning the interests of scholarship athletes, university campuses, the NCAA and the sports public with the incredible revenue potential of college sports. Assigning to universities the intellectual property rights of athletes which play under their names while creating a revenue-sharing model with those athletes would meet this need. Just as occuered with respect to the faculty, such an approach would encourage the further generation of revenue from sports, creating a windfall for many college athletic programs, some of which are strapped for cash, and deliver deserved rewards to the scholarship athletes who play the games.

A revenue-sharing model has served college faculty who conduct research and their home universities very well over more than three-decades. Universities should get to work on adopting a similar model for its athletes, before change is forced upon them, perhaps abruptly.

Thursday, May 7, 2015

Tuesday, May 5, 2015

German TV Crew Investigating FIFA Arrested and Detained in Qatar

A television crew was arrested, interrogated and had its equipment deleted and destroyed by Qatari authorities while filming a documentary about the 2022 World Cup.The reporters were released and their equipment destroyed:

A reporter, cameraman, camera assistant and driver were denied permission to leave the Gulf state for five days after capturing footage of labour camps there for a programme called The Selling of Football: Sepp Blatter and the Power of Fifa.

[Florian] Bauer and his team were arrested on March 27, a day after arriving in Qatar, and were held for 14 hours before being released at 4am the following morning.The press freedom watchdog Reporters Without Borders ranks Qatar 155th out of 180 countries in terms of press freedom. Reporters Without Borders argues that with hosting the World Cup comes certain responsibilities:

Admitting he was “scared”, Bauer said: “There were interrogations by people from the intelligence service who said if I didn’t co-operate with them, it would work badly for me.”

The crew was physically unharmed, which could not be said for its equipment.

Bauer added: “Everything was deleted: phone, hard drives. A laptop got destroyed, got opened by I don’t know who.”

"Any country with major sporting events such as Qatar seeks the international stage, it is also important that global public be allowed to ask questions." (translated)For its part, the Qatari government explained that the arrests had nothing to do with FIFA or the World Cup, but occurred to the fact that filming was taking place without required permits. This seems rather circular as the reporters requested permits to film and were ignored. So they proceeded anyway.

Continuing revelations about the Qatar bid to host the World Cup and working conditions within Qatar continue to hound FIFA and the Qatari government. The latest episode adds to the list. The German documentary is set to air next week. FIFA and Qatar can be sure that it will get many more viewers thanks to the arrested journalists. FIFA has apparently not commented.

Monday, May 4, 2015

A Content Analysis of ESPN's Draft Coverage - Evidence of Racial Bias?

At Vice Sports @A_W_Gordon has a fascinating post on the language used to described football players during 15 hours of ESPN's coverage of the 2015 NFL draft. Content analyses is a powerful tool to reveal focus of attention as well as the key terms used in communication.

Here is a word cloud of terms used by the ESPN hosts only to describe black football players (with the size of the word proportional to its frequency):

And here is a word cloud for those terms used exclusively to describe white players:

Gordon writes:

There is also a substantial academic literature on this subject. For instance:

Here is a word cloud of terms used by the ESPN hosts only to describe black football players (with the size of the word proportional to its frequency):

And here is a word cloud for those terms used exclusively to describe white players:

Gordon writes:

. . . feel free to stare at this for as long as you want, but let's do a quick breakdown. Only black players were described as: gifted, aggressive, explosive, raw, and freak. Only white players were described as: intelligent, cerebral, fundamentally, overachiever, technician, workmanlike, desire, and brilliant.In 2014, Deadspin (Gordon and colleagues) did a similar analysis with similar results.

There is also a substantial academic literature on this subject. For instance:

- Rainville, R. E., & McCormick, E. (1977). Extent of covert racial prejudice in pro football announcers' speech. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 54(1), 20-26.

- Tyler Eastman, Andrew C. Billings, S. (2001). Biased voices of sports: Racial and gender stereotyping in college basketball announcing. Howard Journal of Communication, 12(4), 183-201.

- Billings, A. C. (2004). Depicting the quarterback in black and white: A content analysis of college and professional football broadcast commentary. Howard Journal of Communications, 15(4), 201-210.

- Angelini, J. R., Billings, A. C., MacArthur, P. J., Bissell, K., & Smith, L. R. (2014). Competing Separately, Medaling Equally: Racial Depictions of Athletes in NBC's Primetime Broadcast of the 2012 London Olympic Games. Howard Journal of Communications, 25(2), 115-133.

- Schmidt, Anthony, and Kevin Coe. "Old and New Forms of Racial Bias in Mediated Sports Commentary: The Case of the National Football League Draft." Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 58.4 (2014): 655-670.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)