At Grantland, Malcolm Gladwell discusses the NBA lockout and the psychic benefits of sports franchise ownership:

Basketball teams, of course, look like businesses. They have employees and customers and offices and a product, and they tend to be owned, in the manner of most American businesses, by rich white men. But scratch the surface and the similarities disappear. Pro sports teams don't operate in a free market, the way real businesses do. Their employees are 25 years old and make millions of dollars a year. Their customers are obsessively loyal and emotionally engaged in their fortunes to the point that — were the business in question, say, discount retailing or lawn products — it would be considered psychologically unhealthy. They get to control their labor through the draft in a way that would be the envy of other private sector owners, at least since the Civil War. And they are treated by governments with unmatched generosity. Congress gives professional baseball an antitrust exemption. Since 2000, there have been eight basketball stadiums either built or renovated for NBA teams at a cost of $2 billion — and $1.75 billion of that came from public funds. And did you know that under the federal tax code the NFL is classified as a nonprofit organization? Big genial Roger Goodell, he of the almost $4 billion in television contracts, makes like he's the United Way.

Simon Kuper has made a similar argument about soccer:

That's the paradox of the football industry: so visible, and yet so little. Football's problem is what economists call appropriability: clubs can't make money out of (can't appropriate) more than a tiny share of our love of football.

Perhaps tickets and replica shirts are overpriced, but few fans actually buy them. A Mori poll in 2003 found that 45% of British adults are interested in football, yet on any weekend only about 1.5% of Britons watch a professional game. In other words, most football fans rarely go near a stadium. They watch football only on TV, sometimes at the price of a subscription, or for the price of some pints in the pub. It's a cheap way to have fun.

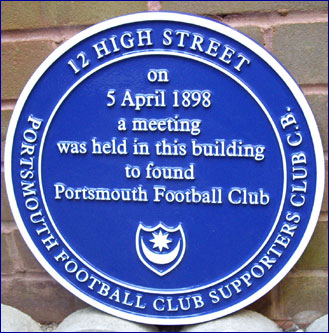

And watching games is only a tiny part of the fans' engagement with football. Fans read newspapers, trawl internet sites, and play computer games. Then there is the football banter that passes time at work and school. All this entertainment is made possible by football clubs, but they cannot appropriate a penny of the value we attach to it. Portsmouth cannot charge us for talking or reading or thinking about Portsmouth. That's why Portsmouth is a small business.

Because clubs are small businesses that spend like big ones, they keep getting into trouble. From 1992 through May 2008, 40 of England's 92 professional clubs had been involved in insolvency proceedings, some more than once. But as Stefan Szymanski and I noted in our recent book Why England Lose, the peculiarity of the football business is that no club disappeared. True, Aldershot went bankrupt in 1992, but supporters simply started a new, almost identical, club. "We must be sustainable," clubs now say, parroting the latest business cliché. In fact they're fantastically sustainable. They survive even when they go bust. You can't get more sustainable than that. Even Portsmouth will most likely always be with us, in some form or other. If football clubs really did collapse under their debts, there would now be almost no football clubs left.

They are too beloved to go bust. Creditors dare not push them under. No bank manager or tax collector wants to say: "Portsmouth is closing. I'm turning off the lights." Luckily, society can keep football going fairly cheaply. The total revenues of European professional clubs for the 2007/08 season were €14.6bn. Tesco turns over four times as much.

Gladwell offers some advice on owners who don't like their profits:

The big difference between art and sports, of course, is that art collectors are honest about psychic benefits. They do not wake up one day, pretend that looking at a Van Gogh leaves them cold, and demand a $27 million refund from their art dealer. But that is exactly what the NBA owners are doing. They are indulging in the fantasy that what they run are ordinary businesses — when they never were. And they are asking us to believe that these "businesses" lose money. But of course an owner is only losing money if he values the psychic benefits of owning an NBA franchise at zero — and if you value psychic benefits at zero, then you shouldn't own an NBA franchise in the first place. You should sell your "business" — at which is sure to be a healthy premium — to someone who actually likes basketball.

No comments:

Post a Comment